This article was first published by the Hinrich Foundation.

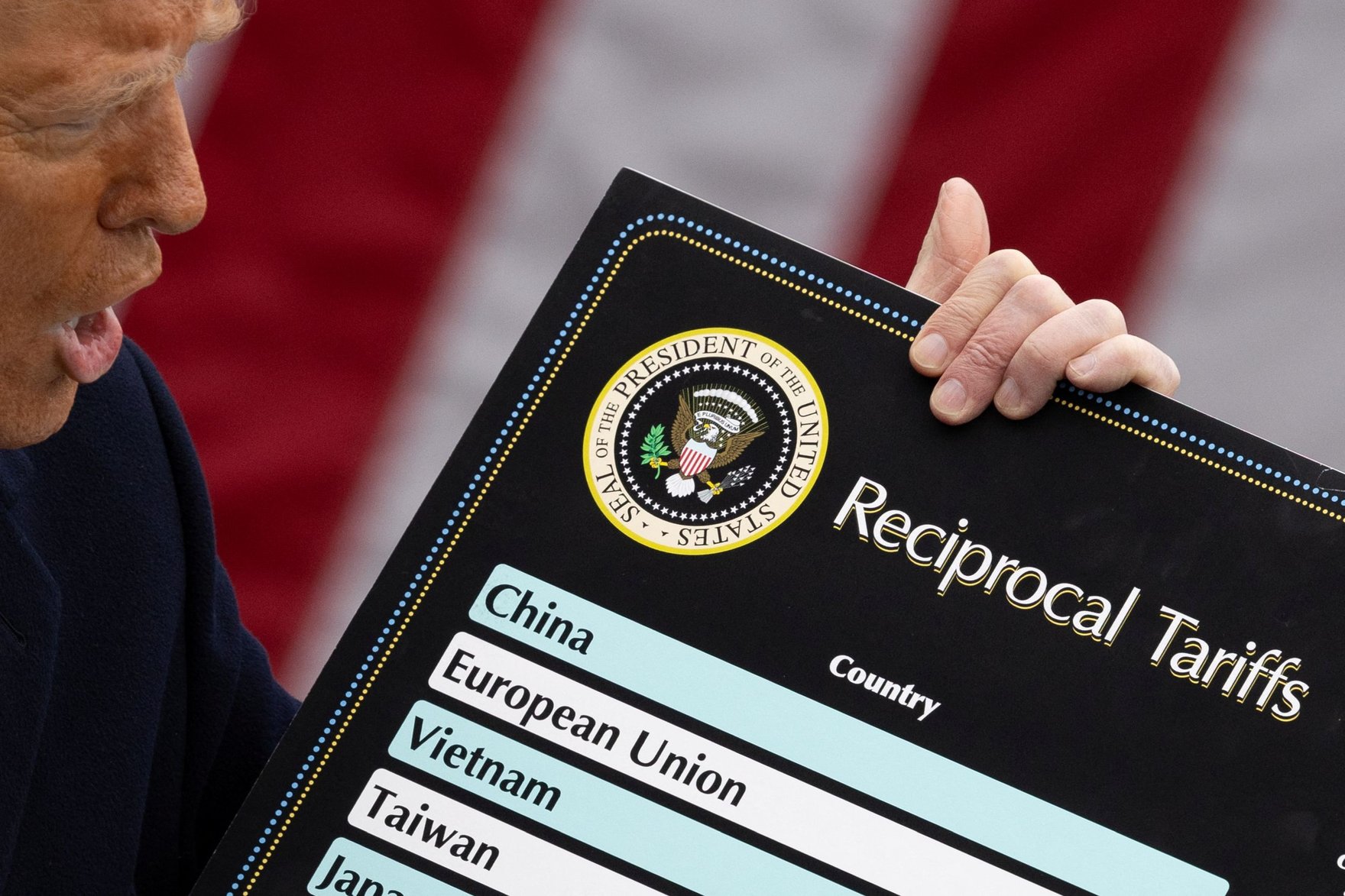

So far, President Trump’s gamble on up-ending global trade appears to be working out in his favour. Trade ministers from around the world continue to vie for preferential access to the US market. In exchange for accepting tariff increases on the goods trade, they obtain advantages over rival exporter economies. The details, durability, and enforceability of these bilateral “napkin deals” remain opaque and most analysis overlooks an urgent and large question on how parties to such bilateral deals could enforce preferences on digital trade – increasingly a major component as a service and intrinsically part of global trade in modern goods.

Bytes, not Atoms: The Challenge of Digital Trade

Trade powered by cross-border flows of data – bytes – is expanding far faster than the traditional trade in physical goods. Moreover, as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) notes, exporting “smart goods” as automobiles, washing machines, and web-connected fridges, increasingly require market access not only for the physical product, but also for their embedded digital services and ongoing support. How are Washington’s trading partners supposed to verify the origin of digital services in the form of bytes coming from America?

Why Rules of Origin Don’t Work for Data

All trade preferences hinge on rules of origin. Was a product made in the country party to the trade deal? What was the origin of the inputs used in its production? And how much value was added in the country from where the final product was shipped?

For physical goods, determining the origin is complex – inputs increasingly and often come from several countries – yet still possible. For bytes, it is simply not. Digital flows can be reproduced in identical copies, at almost zero marginal cost, stored in multiple places, and “shipped” from anywhere simultaneously.

There are no agreed rules of origin for digital trade. The WTO Agreement on Rules of Origin is not applicable to digital flows as it was negotiated when digital trade was in its infancy. So far, WTO members have only agreed on a moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions, which is set to expire in March.

Existing multilateral rules of origin work for goods because they are things that can only be in one place at the time – atoms – and therefore can only be delivered from one place at one time. Bytes behave differently: they replicate like waves in the ocean, making their “origin” impossible to pin down without intrusive surveillance. Therein lies the profound risk of applying the current preferential trade deals driven by Trump to a new world of goods heavily embedded with digital services, a lot of which are dominated by American producers and exporters.

Given the omniscient nature of bytes, only multilaterally agreed rules of origin could prevent a fragmented web of digital firewalls.

The Firewall Dilemma

This creates a profound dilemma. To prevent free riding on the preferences they obtained under Trump’s bilateral deals, foreign governments would need to assert the origin of digital flows embedded in the goods and services they export. The only way for them – and the United States itself as well – to do so unilaterally would be by building digital firewalls, i.e., systems capable of scrutinizing data flows. Technically, this is feasible. China and other authoritarian governments already do it, allowing only state-vetted bytes. Virtual private networks can provide a workaround, but Beijing in particular has proven adept at choking off and shutting down almost all commercial VPNs when it needs to.

Here lies the paradox: In order to exclude China from free-riding on preferences embodied in Trump’s bilateral “reciprocal” trade deals, the US – the very country that claims to lead the “free world” – could end up encouraging its trading partners to adopt China-style digital firewalls.

Toward an Orwellian Trap?

Trump’s trade policy not only contradicts the World Trade Organization’s most-favoured-nation principle, they also risk creating a spaghetti bowl of bilateral digital rules-of-origin, forcing governments to build walls first along the lines of physical goods, then eventually around their digital borders.

Digitalization is dramatically increasing the scale, scope, and speed of cross-border trade. Given the omniscient nature of bytes, only multilaterally agreed rules of origin could prevent a fragmented web of digital firewalls.

China has long restricted cross-border data flows through its Great Firewall. Without multilaterally agreed rules, the world risks splintering into rival digital blocs each with its own version of such firewalls. Trump’s efforts to exclude China from benefiting from US-dictated bilateral trade preferences, in place of multilaterally agreed rules, contemplates normalizing the very same intrusive tools pioneered by the Chinese state.

From Rules-based to Deals-based

The United States once was the chief architect and ultimate guarantor of the multilateral rules-based trading system. It is recasting it into a web of bilateral “reciprocal” trade deals. Through these agreements, Trump seeks to extract selective preferences that he hopes will “rebalance” US trade deficit and prevent China from “trans-shipping” its exports through third countries. Yet, in his attempt to weed China out from global value chains, Trump may be unwittingly pushing America’s trading partners closer to China’s model of state intervention.

Reciprocity: Already in the WTO

The WTO does provide a framework of rules that would have allowed a member-state like the US to increase tariffs beyond its bound rates through “reciprocal and mutually advantageous” bilateral deals1, provided that the new tariff is either extended to all other WTO members (under the MFN principle) or leads to new free trade zones or custom unions.

Alas, these are not preferences that Trump – or indeed successive US administrations – are looking to build upon. The US wants neither new free trade zones nor custom unions. It would prefer a unilaterally imposed system that confer trade privileges to specific partners that are not to be extended to other WTO members, least of all China.

Conclusion: Whither the Open Digital Economy

Countries that once relied on US leadership to keep the internet open could find themselves building their own firewalls to comply with Washington’s reciprocal deals. The result would not isolate China, but instead make China’s governance model widely adopted.

Multilateral cooperation remains the only method to provide the standards required to advance an open digital global economy. The alternative – a web of reciprocal trade deals enforced by digital firewalls – risks locking the world into an Orwellian future, where trade and the internet alike are carved up by political borders.

That is the Orwellian trap we must avoid.