The 2025 NATO summit, happening June 24–25 in The Hague, will be unique in many ways. Many of NATO’s most prominent members have gone through political transitions in the past 12 months, and Mark Rutte will lead a summit for the first time since being named the organization’s new secretary general. With elements such as the strengthening of NATO’s deterrence capabilities, increasing defence budgets and the ongoing support for Ukraine, as well as recent events in the Middle East, likely among the key topics for discussion, we asked CIGI experts and fellows: “In your opinion, what is the biggest strategic question that NATO leaders must answer in the 2025 summit?”

Raquel Garbers, CIGI Visiting Executive

The hostile states are now more dangerous than they would have been.

To deter global war, the allies must restore their ability to win the fight. Meeting that challenge begins with casting aside the deeply flawed mindset they adopted at the end of the Cold War when foreign policy and economic elites assured them that economic interdependence would pave the path to peace and riches. Embracing the fantasy that globalization would pacify hostile states, the allies made two critical mistakes: they allowed their militaries to decline, and they opened their economies to the world.

Seizing their opportunity, the hostile states — China chief among them — nested themselves inside the allies’ economic and industrial systems and set to work using malign trade and investment practices, theft, espionage, sabotage, bribery and extortion to amass the military power that threatens us.

By enabling the hostile states to wage economic warfare against the allies, globalization delivered the opposite of what the foreign policy and economic elites had promised. The hostile states are now more dangerous than they would have been. America and its allies are now weaker than they should have been. And the risk of global war in the nuclear age is more real than it should ever be.

Arresting the slide from today’s economic war into total war requires the allies to come to terms with two inconvenient truths. In failing to arrest the hostile states’ economic warfare against them, the allies have de facto subsidized the war machines that now threaten them. And should they fail to aggressively decouple from their adversaries before they gush billions of dollars into new defence investments, they will soon find that they have made their adversaries stronger still.

Branka Marijan, CIGI Senior Fellow

Strategic leadership now requires more than guns and tanks.

The biggest strategic question facing NATO leaders at the 2025 summit is not simply how to deter adversaries — it is how to hold the alliance together in a world where threats increasingly transcend the military domain.

The war in Ukraine grinds on. The Middle East simmers. Trade disputes among allies fester — all while China steadily expands its global influence. Climate disruptions and Arctic competition, sometimes between supposed partners, add new layers of tension. Meanwhile, private firms are shaping the future of warfare at a pace states struggle to match. Taxpayers are footing the bill for investments in deep-tech firms that promise defence advantages but raise questions about transparency and about who, in the end, really benefits. NATO’s traditional tools, once sharp, now seem ill-suited for a world where power is increasingly networked, digital and diffuse.

This convergence of geopolitical and technological pressures has created a perfect storm for global security and a defining moment for NATO. Leaders must grapple with how a potentially fragmented alliance can respond not only to conventional threats but also to systemic challenges that demand careful diplomacy, foresight and investment in societal resilience.

Complicating matters further is the unpredictability of US engagement. If America retreats, other members will be left to preserve transatlantic cohesion while also defending their own interests.

Strategic leadership now requires more than guns and tanks. It calls for flexible multilateralism, credible capacity building, and renewed attention to trust- and confidence-building measures — areas where Canada, as a middle power, can lead.

Paul Samson, CIGI President

If there is a single top strategic question it would be about defence spending and burden sharing.

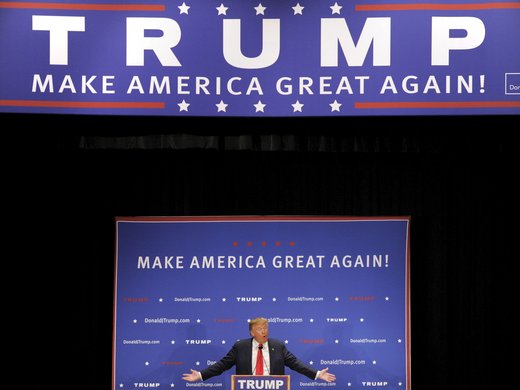

The 2025 NATO summit at The Hague faces many strategic questions around the table, with the backdrop of an unresolved war in the neighbourhood and the wildcard factor of President Trump’s pronouncements at the meeting or an early departure.

If there is a single top strategic question — beyond confirmation of all NATO members’ commitment to collective defence — it would be about defence spending and burden sharing. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, with US prompting, will look to find agreement on an increased target, potentially as high as five percent. Canada’s recent commitment to meet the current two percent target this fiscal year surely foresaw the urgent need for a full course correction.

If massive defence spending in NATO countries is taken as a given for the coming years, this will have huge implications for the industrial base and infrastructure in Canada and other countries as they pivot to turbocharge defence production capacity and do so in new ways for the era of artificial intelligence and cyber conflict. In this context, Canada and others will need to better position “dual-use” technologies that have both civilian and military application potential.

As outlined in a 2024 report to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly, when private actors research and develop technologies for commercial applications, government defence budgets can be relieved of some pressure, and the path to commercialization can also be cheaper due to economies of scale in civilian markets.

On the other hand, technologies controlled by private sector can weaken government control of strategic technologies that have potential military use, as is the case with many new satellite technologies.

Aaron Shull, Managing Director and General Counsel at CIGI

Summit watchers already got a dress rehearsal at the Group of Seven (G7) summit.

The NATO summit in The Hague will expose at least three strategic decision points. The first is the role the organization has in the Ukraine-Russia war. The second is more existential and relates to the future of the organization itself, especially the article 5 commitment to collective defence and spending targets. The third is how the organization plans to deal with emerging technologies.

For the role of NATO in the Ukraine-Russia war, summit watchers already got a dress rehearsal at the Group of Seven (G7) summit held earlier this month in Kananaskis, Alberta. There, the G7 did not issue a joint statement on Ukraine, despite doing so on other pressing matters of international security. This is because the United States did not agree with the other members. I would expect that same outcome from the NATO summit.

Article 5 of the NATO treaty states that “an armed attack against one…shall be considered an attack against them all.” This formerly iron-clad guarantee has now been comingled with defence spending targets. On this, US President Donald Trump has said publicly: “If you’re not going to pay your bills, we’re not going to defend you.” In this regard, the relationship between spending targets and collective defence obligations will take centre stage.

Finally, emerging technologies will require focused attention. Here is a good example: On February 24, 2022, Russia conducted a cyberattack against the Viasat KA-SAT satellite internet service in Ukraine. This incident also disrupted the internet connectivity of tens of thousands of people in Europe (read: NATO members). So the question becomes: When does a cyberattack against a satellite count as an “armed attack” requiring an article 5 response? This, and many other questions related to emerging technologies, remain unresolved.

Wesley Wark, CIGI Senior Fellow

The spending target may be overshadowed by the unknowns of what else the US will bring to the table.

All eyes will be on summit decision making on a new NATO defence-spending target. That may prove a contentious objective with some countries, such as Spain, already voicing objections to the plan to raise the spending target to 3.5 percent plus another 1.5 percent on defence-related infrastructure. Many NATO countries, Canada among them, will struggle to meet such a goal, even if phased in over a lengthy time frame.

But the spending target, which is in line with US demands, may be overshadowed by the unknowns of what else the United States will bring to the table, including a potential drawdown of US forces in Europe, objections to any more forceful action against the Russian so-called “shadow fleet” of tankers used to ship Russian oil to global markets and resistance to any strong statement on NATO support for Ukraine. Depending on the trajectory of the Israel-Iran war, the United States may also try to build a NATO consensus, which would no doubt prove difficult, on the need for military action against Iran.

The United States will not only be the elephant in the NATO room, it will also be the spoiler. For other NATO member states, the challenge will be to navigate the summit to a successful outcome on new spending targets, while avoiding any painful rift with the United States, to ensure its ongoing commitment to the alliance. All NATO states will recall that Trump, during his first term in office, threatened to quit the alliance, one forged by US leadership nearly 80 years ago. NATO will not want the 2025 summit to be remembered as the one that ended the alliance.